Our latest manuscript has now been published online: https://doi.org/10.1093/nargab/lqaf213. It represents one of the main outputs of my first postdoc at the Laukens Lab, so I am very pleased that we were able to bring this work to publication.

At the same time, it is more than just another paper to me. I would like to share why SquiDBase, our resource dedicated to helping the scientific community make the most of raw nanopore sequencing data, is particularly meaningful to me.

How things started

Waiting days or even weeks to read out DNA sequences from organisms such as viruses, bacteria, or humans is largely a thing of the past. Over the last decade, Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) has fundamentally changed how genome sequencing can be done. By marketing portable devices that can read DNA directly from biological samples, ONT has made sequencing faster, more flexible, and more accessible than ever before.

ONT started selling its technology in 2014. Eleven years later, the platform has matured considerably. It is now more robust, more cost-efficient, and easier to use in practice. As a result, nanopore sequencing has moved beyond specialised sequencing centres and into a wide range of settings, from academic laboratories to hospitals and field deployments. This shift has already reshaped the field of genomics, and there is little doubt that its disruptive impact will continue.

My own journey with nanopore sequencing began in 2020. At the time, I was studying bacteria from Ethiopia at the Institute of Tropical Medicine in Antwerp, driven by a broader ambition to make a tangible difference using microbial genomics. Nanopore sequencing offered something that other technologies did not: the possibility to generate rich genomic data quickly and close to where samples are collected. That promise immediately resonated with my interest in applied genomics and global health.

A few years later, around 2023, the focus of my work shifted. The University of Antwerp became my main host institution, and my supervisor, prof. Kris Laukens, started taking a close interest in an often overlooked aspect of nanopore sequencing: the raw signal data produced by the device. Unlike traditional sequencing technologies, nanopore sequencers do not directly output DNA bases. Instead, they generate complex electrical signals as DNA molecules pass through nanopores.

Around that time, we applied for academic funding to explore a shared idea. Our vision was to use computational biology to make nanopore sequencing more cost-effective and, ultimately, more suitable for deployment in low- and middle-income countries, diagnostic contexts, and other resource-constrained settings. As is often the case in research, the vision was ambitious, but we started with modest, concrete steps.

What intrigued Kris about the raw nanopore signal, and what he managed to spark in me as well, was its nature. At its core, the signal is a time series, a type of data that has been studied extensively for decades in other fields. Many established signal-processing and machine-learning techniques could, in principle, be reused or adapted. At the same time, the data is computationally challenging: it is high-volume, noisy, and tightly coupled to rapidly evolving sequencing chemistry and hardware.

So we had enthusiasm, expertise and ideas, but there was just one major problem. Very little raw nanopore signal data was publicly available in a structured and reusable way. This may be because the technology evolves so quickly that datasets become outdated fast. It may also be because the data is simply too large and cumbersome to share easily. Whatever the reason, the lack of accessible signal-level data formed a clear bottleneck for research.

That bottleneck is where the story of SquiDBase begins.

SquiDBase makes raw nanopore data FAIR

Almost all publicly shared sequencing datasets are limited to basecalled FASTQ/BAM files — that is, the DNA sequences that have already been translated from the raw electrical signal. While FASTQ files are indispensable for many applications, they omit the original signal information that lies at the heart of nanopore sequencing. That signal contains rich biological and technical detail, and growing research suggests it can improve basecalling, epigenetic detection, adaptive sampling, and algorithm development more broadly. Yet outside of a few isolated repositories, accessible raw nanopore signal data was scarce and fragmented, especially for microbial datasets and the newer R10.4.1 chemistry that many researchers favour.

To address this gap, we developed SquiDBase — a community-focused, open-access repository for raw nanopore sequencing data. SquiDBase accepts data in the current standard raw format, POD5, along with rich metadata to make datasets discoverable and reusable.

SquiDBase is built around three core principles:

- Open access and findability: Raw signal datasets in SquiDBase are freely available without mandatory logins. Researchers can search, filter, and download raw reads and associated metadata directly from the platform. This level of accessibility is critical for reproducibility and for empowering computational developers to test and benchmark methods on real-world data.

- Privacy and compliance: Raw signal data may contain human genetic information if samples are derived from clinical or metagenomic sources. To ensure broad usability while respecting privacy regulations, I developed SquiDPipe (https://github.com/SquiDBase/SquiDPipe), an automated preprocessing pipeline that removes human or otherwise unwanted reads before deposition.

- Diversity and community contribution: At launch, SquiDBase already includes a curated set of raw datasets from 24 clinically relevant viruses, generated using recent R10.4.1 flow cells in collaboration with our virology colleagues. In addition, two researchers from ScienSano reached out to us and we uploaded their dataset, and one additional researcher from Helmholtz munich uploaded their data. Both datasets were published in papers that also show the additional value of re-using raw nanopore data This initial collection significantly expands the diversity of openly available raw nanopore data, and we continue to encourage contributions from the wider research community.

By providing a centralised repository of raw nanopore signal data accompanied by structured metadata and preprocessing tooling, SquiDBase aims to dismantle a longstanding bottleneck in nanopore research. It creates an infrastructure where algorithm developers, data scientists, and experimentalists can explore the full depth of signal-level information — from basecalling improvement and modification detection to advanced machine-learning applications — under shared standards and open science principles.

SquiDBase in practice

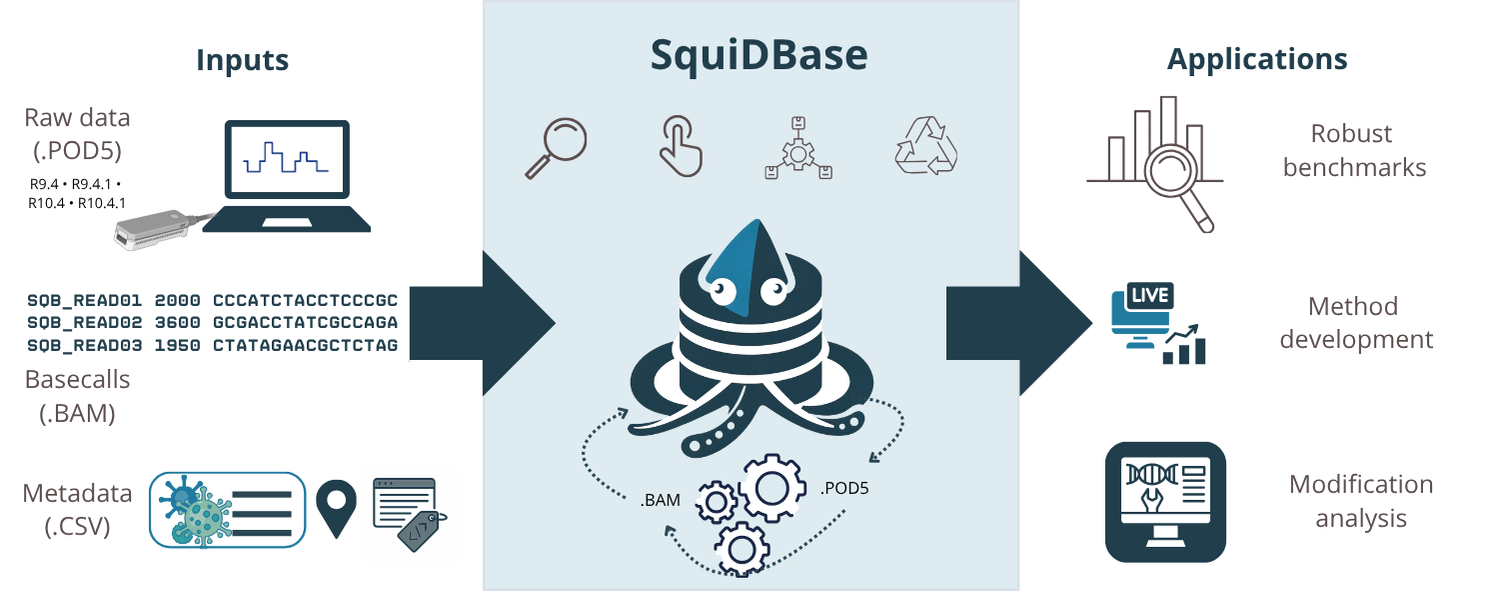

So, what does it do? The general overview is shown below in Figure 1. In Brief, SquiDBase takes raw data, basecalled data, and rich metadata, stores in in a way that is as much FAIR compliant as possible, making it re-suable for several applications including benchmarking bioinforatics tools, developing new methods, and support research such as modification analysis.

Figure 1. Visual abstract from the SquiDBase paper (https://doi.org/10.1093/nargab/lqaf213). The figure illustrates the required inputs to the resource, the storage of raw POD5 files alongside basecalled BAM files, and the design of the repository in accordance with the FAIR principles. It also highlights downstream applications enabled by this paired raw and basecalled data repository.

Below, I outline three short stories illustrating how SquiDBase can be used in practical settings. I hope they resonate with, or inspire, at least some researchers!!

- Improving basecalling accuracy for bacterial genomics: Use publicly available raw nanopore signal data to retrain or fine-tune basecalling models for specific bacteria with unusual methylation patterns. This can improve consensus accuracy, enable reliable cgMLST typing, and support genomic surveillance in low-resource settings. For example: a lab working on a methylation-rich bacterial pathogen retrains a basecaller to reduce systematic errors and obtain typing results that are robust enough for local outbreak investigation.

- Developing algorithms for raw signal classification: Benchmark and develop new computational methods that operate directly on nanopore signal data, for example for species identification, contamination detection, or modification-aware read classification. For example: a bioinformatics group designs a model that classifies reads at the signal level, allowing early detection of mixed samples without relying solely on basecalled sequences.

- Exploring epigenetic regulation in malaria parasites: Reanalyse raw nanopore signal data to detect DNA modifications and compare epigenetic patterns across Plasmodium species. Signal-level datasets enable cross-species analyses and the generation of new hypotheses on regulatory mechanisms and virulence. For example: researchers compare signal-derived modification profiles between Plasmodium species and identify candidate regulatory differences linked to host invasion.

Some final personal reflections

SquiDBase has been one of the central projects of my postdoctoral work at the University of Antwerp’s Adrem Data Lab. Working on it has been genuinely rewarding, in large part because of the people involved. I particularly enjoyed collaborating with our team, and I want to give a special mention to Halil Ceylan, our database engineer. He did an excellent job building the technical backbone of the platform and is the second author of the paper. I still remember Halil’s first days in our group: I did not speak database engineering, and he did not speak biology. Two years later, I am very pleased that we have both gained a deeper understanding of each other’s fields of expertise.

I sincerely hope that SquiDBase will have the impact we envisioned: opening up raw nanopore data for the broader scientific community and enabling new lines of research. Ultimately, my ambition is that this will contribute to making nanopore technology even more accessible and cost-effective, including in low- and middle-income countries, for example through the development of more efficient computational methods.